Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

Exegesis in Thelema is not a passive act of textual analysis or mere number crunching but a transformative engagement with its sacred writings. Interpretation, in this sense, is not about imposing external authority upon the text but about aligning one’s own consciousness with the unfolding of its truths. Thelemic scripture defies the rigid structures of dogmatic exposition, demanding instead a fluid, ever-adaptive approach in which meaning is revealed according to the readiness of the student. Thus, exegesis is not merely an intellectual pursuit but an alchemical process wherein the interpreter must refine their own being to receive deeper insight over and over again.

I know, that sounds really esoteric or like some kind of textbook definition ripped out of the pages of a Gunther exposé on how to read the Holy Books of Thelema, right? It might as well be.

It’s garbage. I mean, I wrote it, but it’s still a garbage take on what exegesis means, whether for Thelema’s so-called “Holy Books” or any other religious text.

The formal definition of exegesis is “critical explanation or interpretation of a text, especially of scripture.” The key word in that whole definition is critical. Nothing else in that whole definition matters until you understand the word “critical.”

I don’t like using Wikipedia for information, but in this case, I think it has one of the most succinct definitions of what I mean by critical: “the process of analyzing available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments to make sound conclusions or informed choices.”1Technically, this is Wikipedia’s definition of “critical thinking,” but the point stands. We don’t merely wish up a personal explanation or interpretation of a text. It’s not just a cool feeling about a text. It’s not some mysterious and mystical mumbo-jumbo to pawn off on your buddies to wow them. There is a whole lot of work that goes into a formal exegesis.

I tell my students every semester: their opinion doesn’t mean shit in my classroom until it becomes an informed opinion. Otherwise, they might as well be talking about their favorite flavor of ice cream.

Exegesis is the manner in which we come up with an informed opinion about something. However, and let’s be clear about this, it’s still an opinion. But it’s light-years ahead of some two-bit mental excrement that Joe Blow decided to grace us with after two beers, a YouTube video, and some obscure number system off the back of a two-thousand-year-old cereal box.

Disclaimer

Let me get something out of the way up front: exegesis is not a one-and-done semester course in seminary, and suddenly you’re an expert. (Same goes for hermeneutics, but I said that last week.) Nor is it possible for me to “catch you up to speed” on the intricacies of exegesis in a single Substack article.

Frankly—and I know I said this last week too—there are far better instructors on exegesis out there. But there are no Thelemic (or pagan or occult) theologians of which I am aware working through actual exegesis for the study of sacred texts that are less than two hundred years old, come from both a ‘revealed-slash-inspired scripture’ tradition and an ‘occult secret society of shared bullshit over a couple dozen decades’ tradition, and through a butch of noise about “a-a-a-authority” when no such conversation is even rational at this stage.

What you have out there is a lot of qabalistic number crunching pretending to be exegesis. I know. I’ve read them all. And I’ve heard all the excuses about how they’re “just as good as exegesis” for beginners. They’re not. They’re really not.

Thelema has a precedent for an exegetical tradition straight from the horse’s mouth, one could say, in that Crowley’s book Equinox of the Gods provides a list of his “formal rules” about exegesis. The utter tragedy is that he ignored nearly every rule he proposed.

Try this one.

Where the text is simple straightforward English, I shall not seek, or allow, and interpretation at variance with it.2Crowley, Aleister, Mary Desti, and Leila Waddell. 1997. Magick: Liber ABA. Edited by Hymenaeus Beta. Weiser Books, 439.

You almost have to stop and reread it again to make sure you actually read it right the first time. How many times have we seen him take the long way around a verse to contort himself into knots to find meaning when the “simple, straightforward English” would have offered something entirely different?

And then there is this one that nearly every Thelemite in existence—including Crowley—ignores in favor of their preferred masterbatory hobby:

I may admit a Qabalistic or cryptographic secondary meaning when such confirms, amplifies, deepens, intensifies, or clarifies the obvious common-sense significance; but only if it be part of the general plan of the “latent light,” and self-proven by abundant witness.3Crowley. Magick, 439 (emphasis mine).

In other words, the qabalistic nonsense is always secondary, not primary, and not someone’s pet project but only with “abundant witness.” And, before that, the qabalistic meaning is only used to confirm, amply, deepen, intensify, or clarify the obvious common-sense significance.

Did you get that? And you can now see how Crowley failed time and time again.

Exegesis is not intended to provide a personal commentary to pander to one’s prejudices.

I covered hermeneutics in Part I of this series last week.

What follows is not entirely original to me, but I participated in its creation. Since it’s still floating around the Internet, I’m leaving it in its original form as well. This one had no introduction, so it was just a list of “rules” with some minor commentary (more like brief thoughts, but we’ll call it commentary to be generous).

However, I have written a new introduction for this version, and I will provide additional critique for a few of the rules based on where I would tweak them for more clarity, as I did with the original copy of A General Approach to Thelemic Hermeneutics.

Overall, I still think this was the best approach to Thelemic exegesis then or since.

A General Approach to Thelemic Exegesis

Exegesis is both a science and an art. It’s a bit like magick. While I think there is a whole field of scholarly endeavor behind exegesis, I also believe that it is solid enough for the layperson to do on their own if approached with a critical mind and an intent to discover significance rather than impose meaning.

We constantly interpret to extract significance from everything around us, but this is about textual interpretation, so I’ll keep my points focused.

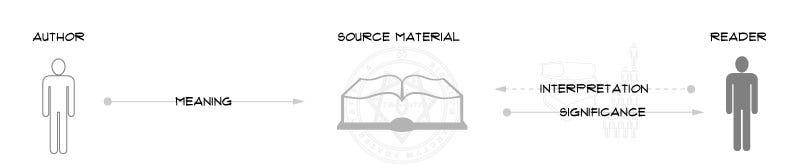

Much has been made of the postmodern ‘death of the author’ in recent decades, and I, as both an academic and an author, reject this notion. The idea that a reader will impose meaning on the material that an author writes is ludicrous. This does not take away from the ability of the reader to extract personal significance from a text. However, there is a difference between meaning and significance that is vital to understand.

This is especially true of religious texts, where we assume that significance can be derived from mystical and hidden “codes” that run between the lines and can be manipulated through dubious and disputed means.

In our age of lazy communication, I may say, “What this text means to me is …”4And we’re going to see this in Osborne’s “hermeneutic enterprise” later when I start talking about homiletic teaching and first-, second-, and third-person “meaning” of texts. but what I am actually communicating is, “The significance of this text to me, as I have interpreted it, is ….”

Exegesis attempts to do one of two things (or both, at times):

-

Recover the meaning of a pericope within the author’s intentions, and/or

-

Discover the significance of a pericope within the reader’s environmental frame.

At no point does an exegesis come down to someone determining what a text means for someone else. We can certainly share what we have learned with someone else, but there is no manner by which we can work with a text and conclusively determine for someone else what it means for them. We can only ever share what it means for ourselves.

Frankly, I think this is the problem with modern occulture, the hubris of thinking that anyone can offer authoritative meaning or even personal significance to someone else outside one’s own experience.5Frankly, if you pay attention to sound Christian theologians, they will tell you the same thing. Sound doctrinal teaching isn’t about interpreting scripture for others—though one may certainly share one’s personal insights with others—but teaching others how to glean insights for themselves. This is where the Letter, Spirit, and Tradition of the Law all meet together to help work toward spiritual formation, a topic that I’ll be pontificating on soon.

That said, recovering meaning is not outside the realm of possibility. Let’s not make the mistake of thinking that because we cannot tell someone else the meaning of a text, that meaning is not discoverable. That would be the other side of that coin of foolishness. It’s the whole reason we have exegesis in the first place. However, it is why exegesis is a careful and considerate science and intricate art as well.

Keeping in mind that exegesis is a never-ending process, let’s discuss A General Approach to Thelemic Exegesis.

-

Examine the context of the manuscript, if available, and always in the original language(s).

Unlike other religious bodies of work based on different ancient languages, the Thelemic Canon is entirely in English, though with a few isolated words in other languages. With the push to have translations of the Holy Books, and specifically Liber AL, any exegetical process needs to be developed with the original language(s) found in the Holy Books themselves.

First, this goes toward AL 3.47a–b, “This book shall be translated into all tongues: but always with the original in the writing of the Beast.” O.T.O. has interpreted “with the original in the writing of the Beast” to mean the original manuscript should be included with each copy of the Book of the Law. It is not often that I agree with some doctrinal policy of O.T.O. regarding Thelema, but in this case, I do. We are one of few religions that have the original manuscripts still existent. We don’t have them readily available for scholars, but they are still protected—in theory, at least.6I actually have a photo that I took of the front piece of the Book of the Law from the Harry Ransom Center from a visit many years ago. It is still my desire that we eventually have full-color reproductions and the ability to have the same scholarly access to the Book of the Law that scholars have to the Dead Sea Scrolls. I think being able to have layered scans of the manuscript would allow us to see all the various marks and re-marks that we know Crowley did over the years.

Crowley doesn’t really address this either, but English isn’t necessarily just the everyday language of the world. Just because once upon a time the “sun never set” on the British Empire doesn’t mean it was always going to be that way. It may be, someday, that English is to some future version of humanity as ancient Greek or Aramaic is today, and we will need to look at the Book of the Law “in the original language” via the “original manuscript” much in the way we attempt to do with the Christian Bible today. Again, fortunately, we have that and continue to print every copy with it.7Also, for purposes of study, I cannot recommend Marlene Cornelius’s Liber AL, an Examination: Liber AL vel Legis, the Book of the Law. An Examination of Liber XXI & Liber CCXX more highly. I haven’t checked to see if it’s still in print, but I would recommend finding it by any means necessary.

More importantly, look at the context of the manuscript compared to the typescript. There are important differences. And if you are so inclined toward the “reading between the lines” and qabalistic meanderings, then spending the time to work with the manuscript will always be in your best interest.

-

Examine the literary context and limits of the pericope.

Understanding context is one of the most insidious downfalls of the Thelemic community, specifically within its modern intellectuals. All kinds of meanings have been attributed to out-of-context quotes.

This is what is called “prooftexting.”8“A single biblical verse cited as a justification for a theological argument or position.” [“proof text” from McKim, Donald K. 2014. The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Second Edition: Revised and Expanded. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.] When someone takes a piece of a verse or a whole verse or a whole section of verses out of context to throw at someone—like, “the slaves shall serve”! or “argue not; convert not; talk not overmuch!”9Christians have what they call “clobber verses.” I think we need to claim the same term for prooftexts like these that are used in the same manner against others for slimy reasons.—This is prooftexting. Frankly, it doesn’t even have to be scripture that is taken out of context like this. It could be any selection from any source. It just so happens that sacred literature is often misused in this manner, so much so that it has a term for it.

A “pericope” is the selection being studied that has a distinct beginning and a distinct ending and forms an independent literary unit. A pericope may contain smaller pericopes or be a part of a larger pericope. It is very important that the pericope be examined and that the selections of scripture not be taken out of context for examination.

This can be tough. I’ll be honest. At what point does the pericope become a prooftext? Context, context, context. When doing a study, you want enough of the scriptural text to ensure proper context but not so much as to drown out the focus.

-

Yes, “the slaves shall serve” is a legitimate pericope. However, it is worthless alone.

-

It needs to be in the context of the rest of the sentence at the least: “Therefore the kings of the earth shall be Kings for ever: the slaves shall serve.” The grammatical structure changes everything about that pericope. (Hint: see that colon in there? Look up what a colon does in a sentence. Or see the last essay on hermeneutics where I broke it down already.)

-

But even more, that sentence needs further context of the surrounding sentences of that same verse: “Yea! deem not of change: ye shall be as ye are, & not other. Therefore the kings of the earth shall be Kings for ever: the slaves shall serve. There is none that shall be cast down or lifted up: all is ever as it was.” That’s even more incredibly helpful.

-

Now we can work on “the slaves shall serve” with some proper context without it being a “clobber verse.”

-

Examine the structure of the pericope.

Interestingly enough, this is a very important feature of Thelemic exegesis. Crowley even scratched his head more than once over the grammatical structure of many things within Liber AL. It is sometimes this structure that is important to understanding a phrase, a sentence, or a paragraph. It could be the tense or the placement of the words in the sentence.

Part of the literary context is the grammatical aspects of the verse itself. One of my favorite scenes in the 1997 film Contact, based on the Carl Sagan book, is between the two main characters.

Palmer Joss: What are you studying up there?

Ellie Arroway: Oh, the usual. Nebulae, quasars, pulsars, stuff like that. What are you writing?

Palmer Joss: The usual. Nouns, adverbs, adjective here and there.

In any pericope, it is the “nouns, adverbs, adjectives here and there” that make all the difference in how we interpret the content and the context. Nothing is written in a vacuum.

Insofar as one might try to wiggle out of the issues of punctuation, Crowley writes in his Commentaries, “The punctuation of this book was done after its writing; at the time it was mere hurried scribble from dictation.” I’d like to be able to say that we too can make the “stops as [we] wilt,” but frankly, that’s not up to us anymore, and tradition has engrained those “stops” where they are now. In short, Crowley has determined the grammatical structure for us, like it or not. We can certainly argue that Crowley, “master of the English language,” didn’t think about his punctuation usage in places and was just careless, but as a Class A text, it’s stuck beyond criticism, and we’re going to now play by the proper rules of exegesis.

See the above example about the colon in “the slaves shall serve” example.

Also—and as a professor, this is merely one of my pet peeves—if you can’t define something, then you can’t hold an informed opinion about it in the first place. This is one of the most difficult parts about occultism today. People think they are having intelligent conversations, think they can talk about grimoires and summon spirits, but they can’t operationalize a definition. Modern occultists use their feelings rather than their minds to talk. Exegesis requires reason, focus, and a sense of operational detachment.

Modern occultism is infected with postmodernism to an inordinate degree. Frankly, most of my first years (right out of high school, and some still in high school) would run circles around the majority of occultists I talk to these days when it comes to critical thinking skills.

-

Review narrative criticisms and other forms of non-historical methods of interpretation.

(Optional)

In some of the Holy Books, there is a narrative form that can be reviewed and should be taken into account by the exegete. In others, a ritual critique might be more appropriate, or maybe a rhetorical critique. There is a rich literary tradition with the occult, and its poetics can be as revealing as its directness.

This was originally labeled as optional. I don’t think any step is optional, per se. It may not be entirely relevant to an exegesis, but I think you should still tap that step and acknowledge it, even if you slide through it. The grammatical-historical approach to exegesis is not the end-all-be-all approach to exegesis that many would like to make it. I think a decade or two ago, there was a huge push to minimize any approach that wasn’t the grammatical-historical approach as flakey. I disagree. I think there are plenty of other exegetical approaches that are just as pertinent to the process that may provide results. Again, context is king. While I think one needs to be mindful not to work towards one’s prejudices, one does need to use the proper tools with the right materials that are in front of them.

-

Review the literary genre and form of the writing.

Looking at the genre of the Holy Book can be as revealing as a direct critique. While it might seem obvious that we are dealing with a religious genre and form, it can be even more helpful to keep in mind that some of the Holy Books are within a separate genre or form in their own right, i.e., visions, parables, rituals, speeches, law, etc. Examining these books while keeping their genre or forms in mind can make a huge difference.

I don’t have much to add to this; I think it is self-explanatory. I would just add a reminder that some texts in the “Holy Books” have multiple genres, such as the Book of the Law.

-

Explore sources, textual allusions, and their use.

This could be said to be an examination of the pericope’s magical, mystical, and mythological aspects. There are many allusions to the Golden Dawn, other religious mythologies, and even literary borrowings from other sources. This is, in a phrase, source criticism. However, in this aspect, the qaballistic or mystical/magical examination of the pericope is also in review.

I think we can get carried away here, but I also think that we don’t do enough to bring these allusions to various mythologies and magical systems into a contemporary understanding and significance. I don’t really care, personally, about the Golden Dawn other than nifty history, but tell me how some nuance of Golden Dawn influence within the Book of the Law has relevance to my everyday life now in a practical manner and you’ll get my attention faster than a fly to a shitpile.

-

Explore the historical context.

This is a broad area of context for the pericope or Holy Book. It is relevant, but not as much—at this time in history—as other areas of exegetical research. It is more valuable in examining the Commentaries of the Prophet or other individuals’ contributions to the literary expansion of Thelema as a whole.

I mentioned this a bit in the essay on hermeneutics. This will be far more important for Thelemites in the future, but it has relevance for those looking at historical documents surrounding the literary contributions to our hierological foundations. Looking at the historical connections can be enlightening, for sure.

-

Review the social-scientific criticisms.

(Optional)

This could be helpful in many ways to the exegesis of any given pericope. Crowley suggested that Thelema was the answer, in a scientific manner even, to social aspects of life —religion, philosophy, etc. It is with this in mind that such criticism could be examined. This is probably the least favorable avenue for most exegetes.

When it comes to theology, most want to stay out of the way of science unless they are glutons for punishment. Religion and science can be good bedfellows but have been antagonists for the last few hundred years or so.

That said, it is my belief that, among other things that I’ll breach another time, a good theologian (especially a Thelemic one) needs to be well-equipped in the natural sciences. Not necessarily proficient in all of them or even in any one of them, but just a rudimentary understanding of biology, climate change, cosmology, evolution, etc, at a conversational level. But also the social sciences: history, politics, psychology, sociology, etc. All of this feeds into our understanding of how to apply what we learn from our hierological texts.

And, once again, I don’t believe this is optional. However, I also believe that much of this can be used not merely for the application of what we learn but in pursuit of discernment in examining Crowley’s Commentaries and the works of other individuals along the way. “Test all things.”

-

Explore key terms.

It is without hesitation that we should be picking up on keywords and terms, key phrases, and passages of meaning. But we should avoid taking on too much here, as this could potentially lead to context issues and misquoting to apply meaning where none exists. The exploration of key terms is one that can provide a great deal of insight. This is one step that easily correlates with others and could be integrated at other levels as well, especially with the qaballistic work mentioned above.

I don’t have much to add here. I would only suggest a warning to be careful of eisegesis—reading one’s prejudice into a text—especially where qabalistic mechanizations are concerned. We’ve all heard the jokes about statistics being able to make up anything. Those jokes apply to the qabala even more so.

-

Examine the broader canonical context.

One must be careful not to examine the canonical context too broadly. Understanding how the pericope or term/concept fits in the larger context of the Holy Books rather than merely its own surrounding text or even within the single Holy Book from which it was extracted can reveal layers of meaning that would otherwise remain obscure. Keep in mind that the exegete should examine the holistic relationship of Thelemic terms and concepts, not pander to merely personal terms or interests.

The Rule and the commentary to the Rule are contradictory, if you ask me. “Check out the Canon, but don’t do it too much!” Stupid.

Once again, with this Rule, context is king. I think that with any word study or pericope study, searching to see if that word or phrase pops up anywhere else and examining that context for further insight is perfectly legitimate and should be helpful. One can always go overboard, but at the moment, I think our range of available texts is small enough that it isn’t too likely to be a problem. Better too much information and pair down to what is relevant than too little information and mistake your analysis for complete.

The only thing I would warn against is trying to compare words that aren’t related just because there is a loose correlation. I’ve said this before: there is only a tenuous relationship between Hadit and Heru-Behdeti due to the ontological construction of the former and the latter as the alleged (most likely modern Freemasonry-esque conception) of the winged disk as the symbol of an eternal soul, but they are not the same. Hadit is not a God—in the “sky daddy” external deity sense—in the Book of the Law. Creating novel connections is not the same as drawing out connections that already exist.

-

Review the history of interpretation, impact, and effect.

(Optional)

Lastly, the passage’s history (if any), interpretation history, and impact on people’s lives, organizations, etc. could be reviewed. This is a good place to review the Commentary of the Prophet and other works, both authorized and unauthorized. This is certainly not a required step, but it is a good one to keep things in perspective.

The more Thelema evolves, I hope we will see more commentaries from intelligent folk out there working through solid exegetical methods. At the moment, there is a lot of garbage commentaries. But—and I say this regularly—at least there are commentaries, even bad ones. This means that people are thinking about the Book of the Law in unique and personal ways. This can only lead to more. The Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists haven’t been any worse off for having multiple commentaries on their sacred texts. I don’t know that they’re better off, but they certainly aren’t worse off.

The idea that more commentaries are somehow harmful to scriptural integrity is ludicrous. There is a strange anti-intellectual strain within Thelema that shits all over people of intelligence and education. Rather than promote a higher quality of effort and output, we continue to rely on YouTube and glamor consumerism to drag Thelema into the pits of dumbtown. Granted, there are some great YouTube people out there. I know I’m making generalizations again. Work with me here.

And for those who keep bringing up that travesty of a political statement, the Tunis Comment, I will also remind you that Crowley anticipated study, research, and commentary by others not only by authorizing it (he approved Louis Culling’s commentary on the Book of the Law) but also by mentioning it in his own Commentaries when referring to an aspect of AL 1:15 that was “to be taken in conjunction with certain later verses which I shall leave to the research of students to interpret.”10Crowley, Aleister. 1923. “The Commentary {to The Book of the Law, unabridged}.” In OS K2, Yorke Collection Papers — Yorke Film 6, Warburg, 189.

Conclusion

This ends my two-part, semi-casual look at the foundations of the critical hierological study of Thelemic scripture. However, I don’t think it’s the end of the journey toward establishing a scholarly approach to the study of our sacred texts. I think it’s just the start of the conversation. These aren’t perfect Rules. No set of rules of hermeneutics or exegesis is ever perfect. But we can refine them and continue to work toward a more useful set over time as we set our face toward producing solid and excellent work in explicating these texts for future generations as wisely as possible.

Love is the law, love under will.

Footnotes

- 1Technically, this is Wikipedia’s definition of “critical thinking,” but the point stands.

- 2Crowley, Aleister, Mary Desti, and Leila Waddell. 1997. Magick: Liber ABA. Edited by Hymenaeus Beta. Weiser Books, 439.

- 3Crowley. Magick, 439 (emphasis mine).

- 4And we’re going to see this in Osborne’s “hermeneutic enterprise” later when I start talking about homiletic teaching and first-, second-, and third-person “meaning” of texts.

- 5Frankly, if you pay attention to sound Christian theologians, they will tell you the same thing. Sound doctrinal teaching isn’t about interpreting scripture for others—though one may certainly share one’s personal insights with others—but teaching others how to glean insights for themselves. This is where the Letter, Spirit, and Tradition of the Law all meet together to help work toward spiritual formation, a topic that I’ll be pontificating on soon.

- 6I actually have a photo that I took of the front piece of the Book of the Law from the Harry Ransom Center from a visit many years ago. It is still my desire that we eventually have full-color reproductions and the ability to have the same scholarly access to the Book of the Law that scholars have to the Dead Sea Scrolls. I think being able to have layered scans of the manuscript would allow us to see all the various marks and re-marks that we know Crowley did over the years.

- 7Also, for purposes of study, I cannot recommend Marlene Cornelius’s Liber AL, an Examination: Liber AL vel Legis, the Book of the Law. An Examination of Liber XXI & Liber CCXX more highly. I haven’t checked to see if it’s still in print, but I would recommend finding it by any means necessary.

- 8“A single biblical verse cited as a justification for a theological argument or position.” [“proof text” from McKim, Donald K. 2014. The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Second Edition: Revised and Expanded. Presbyterian Publishing Corp.]

- 9Christians have what they call “clobber verses.” I think we need to claim the same term for prooftexts like these that are used in the same manner against others for slimy reasons.

- 10Crowley, Aleister. 1923. “The Commentary {to The Book of the Law, unabridged}.” In OS K2, Yorke Collection Papers — Yorke Film 6, Warburg, 189.