1Some of this material was originally published in 2019. It’s been repurposed with permission for this essay.Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

Frankly, if I’m going to start out blunt here, I’m going to say it bluntly: Thelemites have instilled, fostered, and promoted a fear of the word “doctrine” into its culture. But—and here’s the catch—they aren’t afraid of actual doctrine itself. Because they usually don’t know any better.

If I had to ponder a guess, over 90% of Thelemites come from a Christian or secularized Christian-adjacent background and have some real, imagined, or feigned beef with religion. The mere mention of doctrine sends many of them into an emotional apoplectic monologue over the slavery of the soul and how puny, shallow minds are restricted through the need for rules and creeds and interpretations without thinking for themselves—as if that was all religion or doctrine entailed.

It’s enough to make one want to vomit at how lame and intellectually lazy it all sounds.

Of course, the problem with doctrine is that the average layperson tends to fall into one of two extremes: either doctrine is entirely a fossilized crutch, or doctrine is dismissed as untenable vaporware. Little understanding of doctrine’s purpose and structure exists, especially in the infancy stages of spiritual formation.

Defining Doctrine

Doctrine, simply put, is the official teaching of any organization. That’s it. Simple, right? Pick any church. Pick any magical order or initiatory body. (Or, quite frankly, pick any political ideology!) The teachings it puts out are its doctrines.

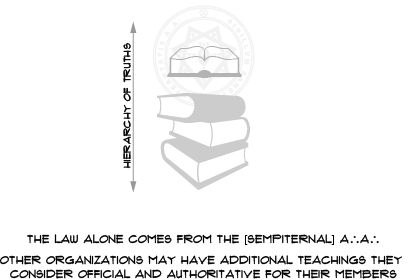

Doctrines always have a hierarchy of truths.

You can always find them in lists. One of the last hierarchies of doctrinal support for an idea I read in a book was (1) Direct Communication of A∴A∴ superiors, (2) Crowley’s Writings, (3) Personal HGA, and then (4) Class A Books.2There is a strange hierarchical problem with this list that took me a while to figure out why it bugged me. Depending on your approach to Thelema—say, mystical adept vs nominal layperson—this list could be very different. However, the doctrinal authority in Thelema is the Book of the Law. But at no point would “Crowley’s writings” come before the so-called “Class A books” or, for fuck’s sake, one’s own “Personal HGA” no matter how you define it! It’s a stepping stone path or ladder of truths.

The Law of Thelema comes from the A∴A∴. No matter how you feel about the mythology of the Great White Brotherhood, this is our mythology at this present time. It is merely one piece of Thelema’s overall worldview.3Though, quite frankly, this could be seen as either a second-order doctrine or a third-order issue. I choosehere to maintain that as we move on.

Other organizations may provide their members with additional teachings that they consider authoritative. However, the Book of the Law is the only text that is authoritative to all Thelemites outside of any organizational mandate or agenda.

However, so many get caught up in the fear of doctrine.

Doctrine comes to us via the Latin doctrina, which comes from docere, meaning “to teach.” Doctrine is, generally speaking, nothing more than the core curriculum of any given organization (or teacher, for that matter).

If we’re going to be frank about all this, then every YouTube, Patreon, and Substack influencer out there is “teaching” you their specific views, which constitute the doctrines to which they adhere and are passing along to you.

The key, however, is whether the doctrines being taught can be supported by the key texts to which they refer and in which they find their legitimacy. This gets into the science and art of exegesis. The number of Thelemites that have any kind of formal training in exegesis can be counted on two hands. I jest. Sorta. Not really. What is passed off as exegesis in Thelemic circles over the last three decades is little more than qaballistic masturbation and finds in itself far more personal ball-scratching than the exposition of truth.

Doctrine in History

While St. Augustine (354-430) is often credited with having written, unitatem in necessariis, in non necessariis libertatem, in omnibus caritatem [unity in essentials; in non-essentials, liberty; in everything, charity], it is likely the more recent work of Marco Antonio de Dominis (1560-1624) in his book, De Republica Ecclesiastica.4Much scholarship around the quote also provides evidence for attribution to Rupertus Meldenius (c. 1582-1651) who likewise developed a twofold system around essentials and nonessentials; see Schaff, Philip. 1980. History of the Christian Church, Volume VII.: Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. Eerdmans. In the early centuries of the Christian Church, theologians typically only debated what they felt essential to the stability of Church doctrine and tossed the rest. The idea of weighing in doctrinally on culture wars just wasn’t part of the Church’s mission.

Prior to the 1970s, in fact, the idea of a demarcation between anything other than essential and nonessential doctrines of the Christian community was absent from theological discussions. Quite frankly, the theological landscape of the time did not demand much more than “this is vitally important” and “that’s just the way we do it”—though, admittedly, the debate on which doctrines should be in what category has raged throughout history.

Times change. More complex issues rise to the surface and get in the way of conversation, even among those who agree on the subject matter more often than not.

In 2004, Albert Mohler, president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, proposed a three-tier system to help deal with theological issues that surfaced within contemporary Christianity and for which the previous two-tier system was lacking. He rightfully called it “theological triage” in the pursuit of ecumenicism within the Christian community toward “strategizing which Christian doctrines and theological issues are to be given highest priority in terms of our contemporary context.”5Mohler, R. Albert, Jr. 2017. “A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity.” AlbertMohler.Com. November 13, 2017. https://albertmohler.com/2004/05/20/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity-2/.

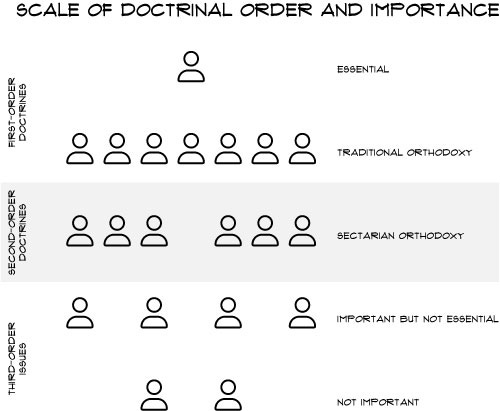

Mohler’s outline offers three levels of theological urgency: first-order doctrines, second-order doctrines, and third-order issues.6First- and second-order information is also used within the field of ethnography where (loosely speaking) first-order information is “just the facts” and second-order information is the “interpretation of the facts.” While not typically addressed outside of specific academic studies in ethnography, third-order information could be seen as the “interpretation of the interpretation of the facts.” One might see a correlation here as well. This is not an isolated view of doctrine either, as Grant Osborne, in his seminal work The Hermeneutical Spiral, offered up a similar breakdown of cardinal doctrines, denominational distinctives, and noncardinal doctrines.7Osborne, Grant R. 2006. The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. IVP Academic, 399-402.

I prefer this breakdown to Mohler’s, but the first-, second-, and third-order language is easier for laypeople to comprehend and use in the course of conversation.

In their attempt to move the doctrinal debate away from emotional invectives and into the realm of academic discovery, both Osborne and Mohler laid the foundation for a more dispassionate approach to the complexities of doctrinal understanding. I find these to be just as relevant in our larger community today as they have been within the Christian community in the last two decades, and yet it is my view that this is where Thelemites miss the boat on doctrinal depth and debate.

It is important to note that those who fancifully wish for Thelema not to be a religion do so against all rational evidence to the contrary. Almost all—if not, in fact, all—of the elements that define religion historically, sociologically, psychologically, philosophically, functionally, phenomenologically, theologically, and critically can be found within even a superficial examination of Thelema. A deeper dive leaves no doubt. [from ‘Thelema: A Religion?—Who’s Still Afraid of Crowley’s Big Bad Wolf?’]

I once argued that using Mohler’s approach would be an excellent framework for harmony and coherence in the larger Thelemic community while providing for a breadth of distinction among individual groups of Thelemites. It would allow for an understanding of what unites us as Thelemites and what can be areas of disagreement without disharmony rather than subjugate the Law to an authoritarian dogma of institutional power.

I remain convinced that could be and should be the case today in pursuit of a focus on harmony rather than discord.

But this also provides a good way for new and young (spiritually speaking) Thelemites to gauge what is important in focus when it comes to conversations among the Brethren who enjoy the pontification of deeper thoughts or just those who like the sound of their own voice.

Importance of Doctrine

However, doctrine plays an important role in an individual’s spiritual development, especially during spiritual infancy.

First, think of individuals as plants. It’s a crude metaphor, but it works—especially in light of so many metaphors of communities as gardens.

Many plants need support when they start to grow. Not all, but many. Think of doctrine as the trellis that supports new plants and gives them stability as they grow. Most plants will eventually outgrow that support, but some won’t, and that’s okay, too.

Granted, some plants don’t need support at all when they start to grow. That’s fine. Others start to grow and are deformed because they don’t have proper support or any support at all. They get pulled up and mulched.

Thelema is full of doctrine. Some of it is important. Some of it is miniscule. Some of it is complex. Some of it is so complex that misunderstanding could deform one’s understanding to the point that it could be damaging to spiritual formation in the long term.

Having a solid doctrine is important, especially when starting out. Maybe you’ll outgrow it. Good for you. Maybe you’ll mutate it into something personal. Excellent. But you won’t be able to avoid it. That much, I can promise.

You can work on denying doctrine as a Thelemite, but you can’t sidestep it. It’s like dogshit in the dark. I mean, you go around spouting it constantly. “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Doctrine. “Love is the law, love under will.” Doctrine. Even that stupid line that you can’t properly parse because you’re grammatically illiterate and are always flinging around at others about “The slaves shall serve”? Doctrine. Someone taught you something about each one of those verses—even if it was Crowley’s Commentaries. Yup. You guessed it! Doctrine.

Yeah. I know. I can hear the arguments swelling already. But what you’re pissed about is dogma.

Take that dogshit up with O.T.O. because dogma is a whole different mess to scrape off the floor another time.

Warning about Extremes

I know I haven’t defined some of these terms yet, but I want to wave a big red flag upfront. I think it’s important to get this out of the way so you will remember it as we go through the definitions. Extremism, whether from the Right (Fundamentalism) or the Left (Liberalism), is not the way we want to proceed. We’ve had enough of it in just over 100 years. We don’t need more—though I’m quite sure we will.

I find Mohler’s comments about the particular extremes in the theological spectrum to be as succinct as they are accurate, and they serve as a warning for us all: “Fundamentalism […] is the belief that all disagreements concern first-order doctrines. Thus, third-order issues are raised to a first-order importance.”8Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.” Conversely, he offers this observation of the other extreme, saying, “The mark of true liberalism is the refusal to admit that first-order theological issues even exist. Liberals treat first-order doctrines as if they were merely third-order in importance, and doctrinal ambiguity is the inevitable result.”9Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.”

We find ourselves looking into the mirror here as we watch one extreme through the fundamentalist/magisterium approach and the opposite extreme through the outliers of the radicalization of individualism10One observation about these two extremes is that they are both outliers when examined in the context of the greater Thelemic community. As with most religious movements, the majority of individuals appear to exist in the median of doctrinal opinions.—though if we are going to err in the area of doctrine, may we always fall closer to the liberal side than the fundamentalist side.11Fundamentalism and liberalism in this context should not be confused with the political spectrum of such words. A doctrinally conservative approach also would be—pun intended—fundamentally opposed to fundamentalism.

Doctrinal Triage

Let’s briefly examine Mohler’s three categories12Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.” and, with only a slight rewording, use them in relation to the Thelema.

• First-order doctrines are those hierological issues (or doctrinal issues, if you prefer that phrase) that would include doctrines most central and essential to the Law of Thelema.

• Second-order doctrines are distinguished from the first-order set by the fact that Thelemites may disagree on the second-order issues, though this disagreement may, and most likely will, create significant boundaries between adherents, though always without a loss of identity. When Thelemites gather themselves into organizations and sectarian forms, these boundaries become evident.

• Third-order issues are those things over which Thelemites may disagree (even heatedly) and remain in close fellowship, even within local groups and organizations.

For Osborne, these would be cardinal doctrines, denominational distinctives, and noncardinal doctrines, respectively.

What should be apparent in Mohler’s breakdown is that at each level, the emphasis is on the unity and identity of the larger community. It is what he even titles a ‘call for … maturity.’ Looking past the unity of first-order doctrines into second-order doctrines and third-order issues, we can see definitively that the focus is on acceptance, continuity of identity, and fellowship among individuals and groups, even in spite of disagreements. It is, quite frankly, a doctrinal pax templi.

Considering that Thelema doesn’t quite yet rise to the level of any formal or Traditional Orthodoxy—to the chagrin of O.T.O., to be sure, and despite their attempt to create their own Sectarian Orthodoxy raised to the level of Essentialdoctrines—this still shows an example of a way of looking at this issue of doctrinal importance.

Separating Thelemic Doctrine

Yet the question inevitably comes up as to what constitutes a doctrine of the first-order (essential) or second-order (sectarian) or what may be regarded as a third-order issue (who gives a shit).

-

We could certainly start with the affirmation that Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law [AL 1.40c] as a first-order doctrine. It is, after all, the central tenet of Thelema.13This verse constitutes the central tenet of Thelema, even though, from a philosophical perspective, it requires certain underlying axioms to be truthful. It is not Thelema’s first axiom nor self-evident in isolation; cf. Balk, Antti P. 2018. The Law of Thelema: Aleister Crowley’s Philosophy of True Will. Thelema Publications.

-

We would be hard-pressed not to affirm “Every man and every woman is a star” [AL 1.3] as a first-order doctrine if not one of the first first-order doctrines, since our central tenet requires this premise.

-

We could bring up the necessity and sufficiency [these are technical theological terms] of the Book of the Law as a first-order doctrine.

-

We could add the discovery and pursuit of True Will/pure will as a first-order doctrine, while the methodology of that pursuit could be a second-order doctrine, and “True Will” or “pure will” as the correct term would be an example of a third-order issue that resides within a first-order doctrine (I mean, it’s truly a “who gives a shit” issue so long as we all know what we’re talking about regardless of the term used).

For the most part, merely as a small sample of examples, these seem like common sense for common ground with minimal controversy.

-

The sacredness or authority of additional Class A texts beyond the revealed text of the Book of the Law is an example of a second-order (sectarian) doctrine. This may be one of the most controversial topics—hence, why it would be a second-order doctrine—since some will find the addition of Crowley’s inspired writings to be necessary for their institutional purposes and teachings and others will find they are without any additional import beyond exemplary guides of an Adept on the individual path of the Great Work.

-

The addition to the A∴A∴ curriculum and classification thereof is entirely that of a second-order doctrine—though I would argue in a different forum that this could be (and probably should be) reduced to a third-order issue altogether.

-

That said, all discussion of Authority outside of the Book of the Law and its first Prophet is second-order doctrine.14This brings up, however, a short diversion into the topic of Authority. While it is not the scope of this essay to explore the concept and form of Authority itself, it needs to be said clearly that no institution can offer Universal Authority within the confines of the Law of Thelema. To reduce the idea of Authority to a petty challenge between organizations is to betray such a complex topic for little more than personal nuance. [see Readdy, 2018, One Truth and One Spirit.]

I will offer some thoughts later in the year based on the tripartite breakdown found in the ‘Refuge’ configuration of the Letter of the Law, Spirit of the Law, and Tradition of the Law, which I think provides a more useful approach to Authority.

Such diversity in approach can certainly be found within sectarian lines without the loss of identity of any individual Thelemite. However, it still creates distinctive lines of difference between sects.

When I examine various online conversations—and look back at lots of community discussions—I see third-order issues (anyone remember the online arguments over “hot-tub free love” and polyamory back in the day?) and even institutional dogma [i.e., entrenched second-order doctrines] stretched as first-order doctrines, sometimes subtly, sometimes directly.

Growth always happens in stages. Development happens gradually and individually. Having a grasp of the essentials provides a sense of stability while offering the anchor for exploring additional areas of growth, whether that be in a sectarian direction or some individualized path. But getting ahead of ourselves and trying to inflict doctrine beyond the essentials on young (spiritually speaking) minds is an atrocity. Allowing for natural growth allows for healthy, independent development.

Identity and Doctrine

I’ve said this in the past, but the Book of the Law establishes a Thelemic identity. This isn’t the place to pontificate over how that identity might be constructed, but I think it’s important to note that it exists at all. There is a unity to that identity. There is an us in some sense, even if it is only by virtue of acknowledging the centrality of the Book of the Law in our cultural formation. I believe it’s more than that, but I’ll present some thoughts on identity at a later time.

However, I believe that part of that identity is shaped by the acceptance of a core set of essential doctrines. While I think we can certainly disagree as to the number of doctrines in that core set, I think the majority of us would agree to a significant number of them outright, such as the ones I presented above.

Conclusion

Unitatem in necessariis, in non necessariis libertatem, in omnibus caritatem.

Unity. Liberty. Love.

Oh, I know, the last is usually translated charity, but I like love. Love is the law, after all.

Unity in the essentials—that which is our first-order doctrines, the essentials. Eventually, I predict, Thelema will have a solidified orthodoxy. I think we’re probably a good fifty to a hundred years away from that now. The reason I say that is because we lack serious theologians writing and communicating, debating together over serious topics. Right now, we have very unserious people spewing bullshit into the aethyrs without the slightest care for accuracy, much less a community of communication at a level of thoughtfulness. It will take cultivating gardens instead of herding cats to shape Thelema for the future. It will take brewing small batches, if you’re into that metaphor instead, rather than trying to manufacture whole brands. And so far, quite frankly, Thelema has been more about people developing their brands than developing the Law into the world around us.

But for any of that to happen, we also will have to learn how to respect each other, both individually and institutionally.

I once suggested it was time to change the conversation. I submit that now is the time to begin the conversation as to what actually constitutes those first-order doctrines that unite us all, that which is both outside institutional power plays andindividual nuances. It is not something that will be resolved in a single committee. This discussion in the greater community needs to happen through the boots on the ground rather than through any magisterial dictate.

I don’t have the answers for how that should happen; I’ll tell you that much.

When all is said and done—even though doctrinal discussions are never truly all said or done if the Christians have taught us anything in this regard—despite the radical individualists crying betrayal or institutions declaring authority within their own impotent fiefdoms, I truly believe there will be some who are shocked by the results.15“The higher our attainment, the more closely will our points of view coalesce, just as a great English and a great French historian will have more ideas in common about Napoleon Bonaparte than a Devonshire and a Provençal peasant” [Crowley, Aleister. 1989. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. Edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant. Arkana, 213].

Likewise, the closer we get to the source of our doctrine, the closer we can see ideas take on a particularly common significance, even if the words appear to be different.

Conversely, I also think there will be those who abuse their assumptions since catchphrases and slogans are easier than doctrines and truth-claims, that there will be those who still remain grounded in the assumptions about the “Aeon of the Child” (while missing the “Crowned and Conquering” part) as something immature, “innocent,” and fleeting in attention span. There will always be those who think the outliers within the radicalization of individualism are an accurate representation of the doctrinal mean. There will always be those who proclaim the Law of Thelema, as such, existing before the Book of the Law. There will always be those who bemoan the idea of the inevitability of sects within the community of Thelema.

It makes no difference. Radical outliers of the last two thousand years did not fold Christianity into itself. Such in our own time will not shake the firm foundation of the New Aeon either.

Love is the law, love under will.

Footnotes

- 1Some of this material was originally published in 2019. It’s been repurposed with permission for this essay.

- 2There is a strange hierarchical problem with this list that took me a while to figure out why it bugged me. Depending on your approach to Thelema—say, mystical adept vs nominal layperson—this list could be very different. However, the doctrinal authority in Thelema is the Book of the Law. But at no point would “Crowley’s writings” come before the so-called “Class A books” or, for fuck’s sake, one’s own “Personal HGA” no matter how you define it!

- 3Though, quite frankly, this could be seen as either a second-order doctrine or a third-order issue.

- 4Much scholarship around the quote also provides evidence for attribution to Rupertus Meldenius (c. 1582-1651) who likewise developed a twofold system around essentials and nonessentials; see Schaff, Philip. 1980. History of the Christian Church, Volume VII.: Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. Eerdmans.

- 5Mohler, R. Albert, Jr. 2017. “A Call for Theological Triage and Christian Maturity.” AlbertMohler.Com. November 13, 2017. https://albertmohler.com/2004/05/20/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity-2/.

- 6First- and second-order information is also used within the field of ethnography where (loosely speaking) first-order information is “just the facts” and second-order information is the “interpretation of the facts.” While not typically addressed outside of specific academic studies in ethnography, third-order information could be seen as the “interpretation of the interpretation of the facts.” One might see a correlation here as well.

- 7Osborne, Grant R. 2006. The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. IVP Academic, 399-402.

I prefer this breakdown to Mohler’s, but the first-, second-, and third-order language is easier for laypeople to comprehend and use in the course of conversation. - 8Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.”

- 9Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.”

- 10One observation about these two extremes is that they are both outliers when examined in the context of the greater Thelemic community. As with most religious movements, the majority of individuals appear to exist in the median of doctrinal opinions.

- 11Fundamentalism and liberalism in this context should not be confused with the political spectrum of such words. A doctrinally conservative approach also would be—pun intended—fundamentally opposed to fundamentalism.

- 12Mohler, 2017, “Theological Triage.”

- 13This verse constitutes the central tenet of Thelema, even though, from a philosophical perspective, it requires certain underlying axioms to be truthful. It is not Thelema’s first axiom nor self-evident in isolation; cf. Balk, Antti P. 2018. The Law of Thelema: Aleister Crowley’s Philosophy of True Will. Thelema Publications.

- 14This brings up, however, a short diversion into the topic of Authority. While it is not the scope of this essay to explore the concept and form of Authority itself, it needs to be said clearly that no institution can offer Universal Authority within the confines of the Law of Thelema. To reduce the idea of Authority to a petty challenge between organizations is to betray such a complex topic for little more than personal nuance. [see Readdy, 2018, One Truth and One Spirit.]

I will offer some thoughts later in the year based on the tripartite breakdown found in the ‘Refuge’ configuration of the Letter of the Law, Spirit of the Law, and Tradition of the Law, which I think provides a more useful approach to Authority. - 15“The higher our attainment, the more closely will our points of view coalesce, just as a great English and a great French historian will have more ideas in common about Napoleon Bonaparte than a Devonshire and a Provençal peasant” [Crowley, Aleister. 1989. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autohagiography. Edited by John Symonds and Kenneth Grant. Arkana, 213].

Likewise, the closer we get to the source of our doctrine, the closer we can see ideas take on a particularly common significance, even if the words appear to be different.